Routines and Rituals

Reflecting on repetitiveness in our daily lives through two uneventful movies: Paterson and Perfect Days.

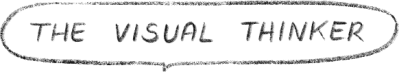

Most mornings, Michelle and I begin our day in much the same fashion: Pecco wakes us up early to climb into bed, we sleep for a little longer if we can, and then my alarm goes off. I get out of bed and head to make our coffees, the sharp thud of the steamed milk pitcher is Pecco’s Pavlovian signal that it’s time to head to the kitchen for his ‘puppuccino’ (a little dose of hot frothed milk in his food bowl). Our fancy-schmancy new espresso machine has been the catalyst for this ritual. Its relative recency is likely the reason for our continued delight at a simple cup of coffee. One might call this a ‘routine,’ a word that has always had a monotonous connotation and one that I spent much of my life trying to avoid.

Our morning ritual… or routine?

Two films changed how Michelle and I view them: Perfect Days (2023) and Paterson (2016). For those unfamiliar with this alliterative duo, I’ll begin by saying I firmly recommend watching them both – not only to connect with this essay but because they are beautifully made bits of cinema that push back against an era of ever-increasing fireworks in the CGI-packed films of the modern age. If you’d like to watch them later and want to read this now: worry not, there will be no spoilers in this essay as there is virtually nothing to spoil. Nothing really happens in either film, at least in terms of what we’ve come to expect from movies.

Each examines the life of a blue-collar public service worker. We see only a short span of their lives – in Paterson merely a week, Perfect Days perhaps a couple. While styles differ, their cores remain the same: a focus on the daily routines of men with jobs that one could call ‘under-appreciated.’ Paterson, the protagonist who shares his name with the film, is a city bus driver with a passion for poetry. Hirayama, a toilet cleaner in Tokyo with meticulous attention to detail. The format is as follows: we follow along with each day as Paterson and Hirayama rise, complete their routines, and head to work. Both men carry a certain dignity in their labor, especially the Tokyoite, who cleans with an almost obsessive level of dedication. They take the same lunch break every day. They move through the workday with unfluctuating regularity.

Their evenings, too, are repetitive: Hirayama bikes to the izakaya spot in a subway station near his house for some noodles and a drink while watching a bit of baseball. Paterson returns home and listens to his partner recount her day before walking the dog and stopping for a beer at the same bar each night.

That’s basically it. We learn a bit more about their lives and various events carry short plots in each film, but the majority of the screen time is dedicated to routines. On paper, I’ve described a pair of movies that would seem utterly boring. And perhaps they are boring in a sense. These men live boring lives and yet neither seem bored. They transform daily life into something more meaningful. They’re turning routines into rituals.

Hirayama’s morning routine

It’s tempting to attribute this shift to the quality and dedication of their work. But no, the key is not in the quality of their work but in their outlook on it. It’s the sense of meaning. Each seems to feel an importance in his role. Hirayama, despite getting little visible recognition for it (he’s often not noticed by those using the public bathrooms), seems to appreciate his work as part of a larger effort to care for the place in which he and his fellow Tokyoites live. Or perhaps he is just obsessed with things being clean, who am I to say? In any case, he sees value in it. Given this, he is patient and thoughtful in going through the motions. At no point, does it feel like he looks at work as something he must get through, but rather sees it as something he is doing.

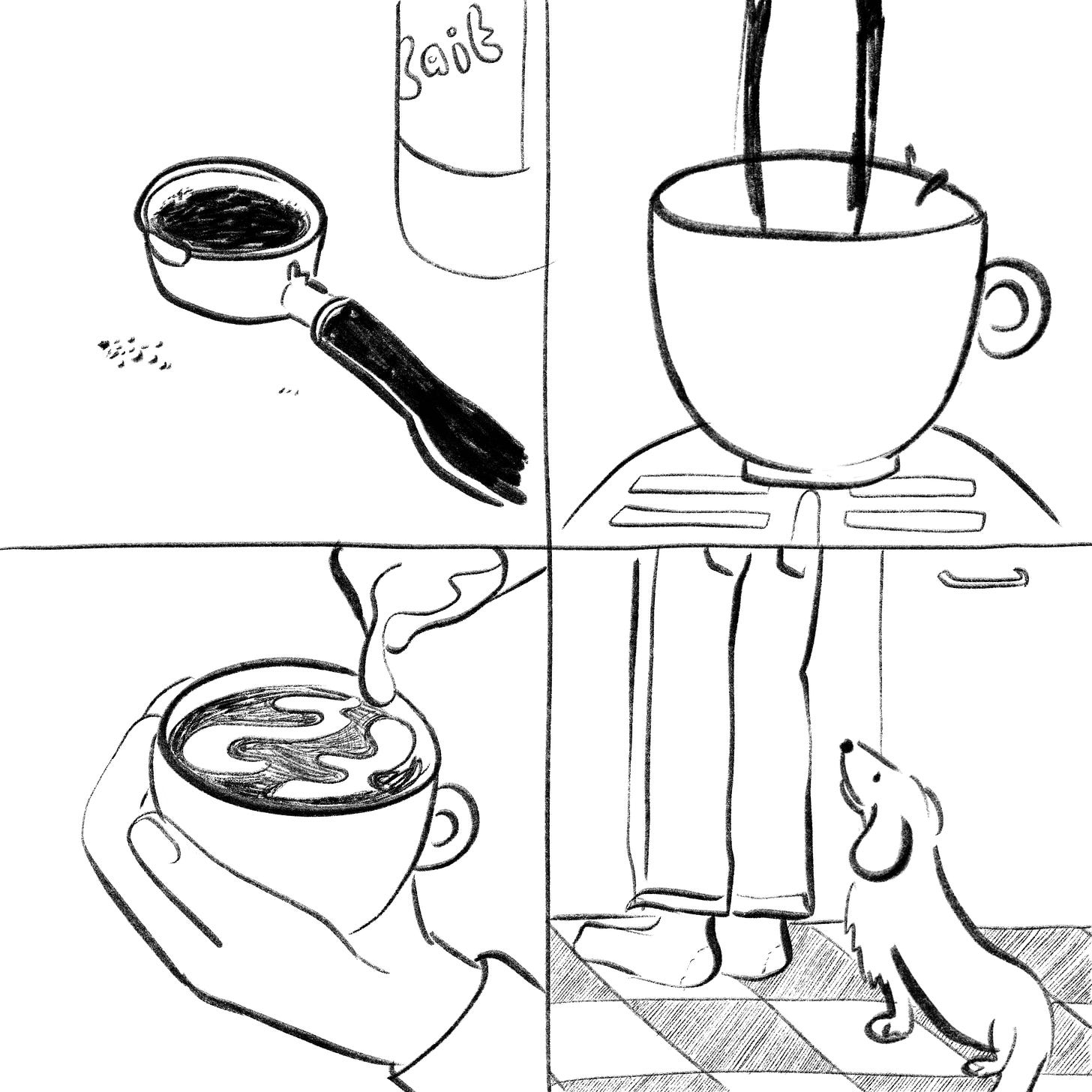

Work incorporates a large portion of both films, but where we see both men flourish is in the spaces in between. Paterson wakes early each morning of his own accord, relying on an internal alarm clock to signal the start of the day. He has a moment of peace walking to the bus station. His lack of smartphone means there is no screen to distract him. In fact - there are no screens in his entire life, as far as we get to see. Hirayama, meanwhile, wakes and puts away the previous evening’s book. He tends to his facial hair and carefully waters his collection of plants before purchasing an iced coffee from a vending machine and heading to his first stop on the route of public restrooms. Each of these tasks receives his full and undivided attention. Both men follow, by definition, a routine. Once more, though, these processes are not rushed nor dragged through. They are comforting in their familiarity and calming in their singular focus.

Paterson’s morning routine

I’m aware I’m getting a bit ahead of myself, here. I’m inferring a lot about two men who say very little about how they feel or what they think. Paterson and Hirayama are stoic and soft-spoken. Any inclination that we have that they appreciate or love their jobs is ultimately coming from us, the viewers. We must take these Paterson and Perfect Days for what they are - films. They are imperfect and they are especially limited in scope. In the former, it never rains and we see none of the chaos nor anger that often occurs on public transport. The latter, while more melancholic, is almost fetishistic in its gaze on Japan, playing to our presumed stereotypes about the nation’s values and honor. This is slice-of-life stuff. It is easy for us to see the simplicity in their repetitive routines and assume that the space in their minds is equally uncomplicated. We get hints that things might be more complex thanwe though in rare releases of emotion near the end of each film (no spoilers, don’t worry!). But for the most part, both film experiences are quite calming.

So, movies aren’t reality. Hardly a groundbreaking realization. This does not mean, however, that we cannot strive to be more like these men. Paterson and Hirayama, while fictional are not entirely unrealistic figures. We can admire their patience, dedication, and mindfulness without idealizing manual labor or simplicity. And while we cannot go too far as to presume they are satisfied with their jobs, we can be inspired by the ways in which they pursue their passions with focus and clarity.

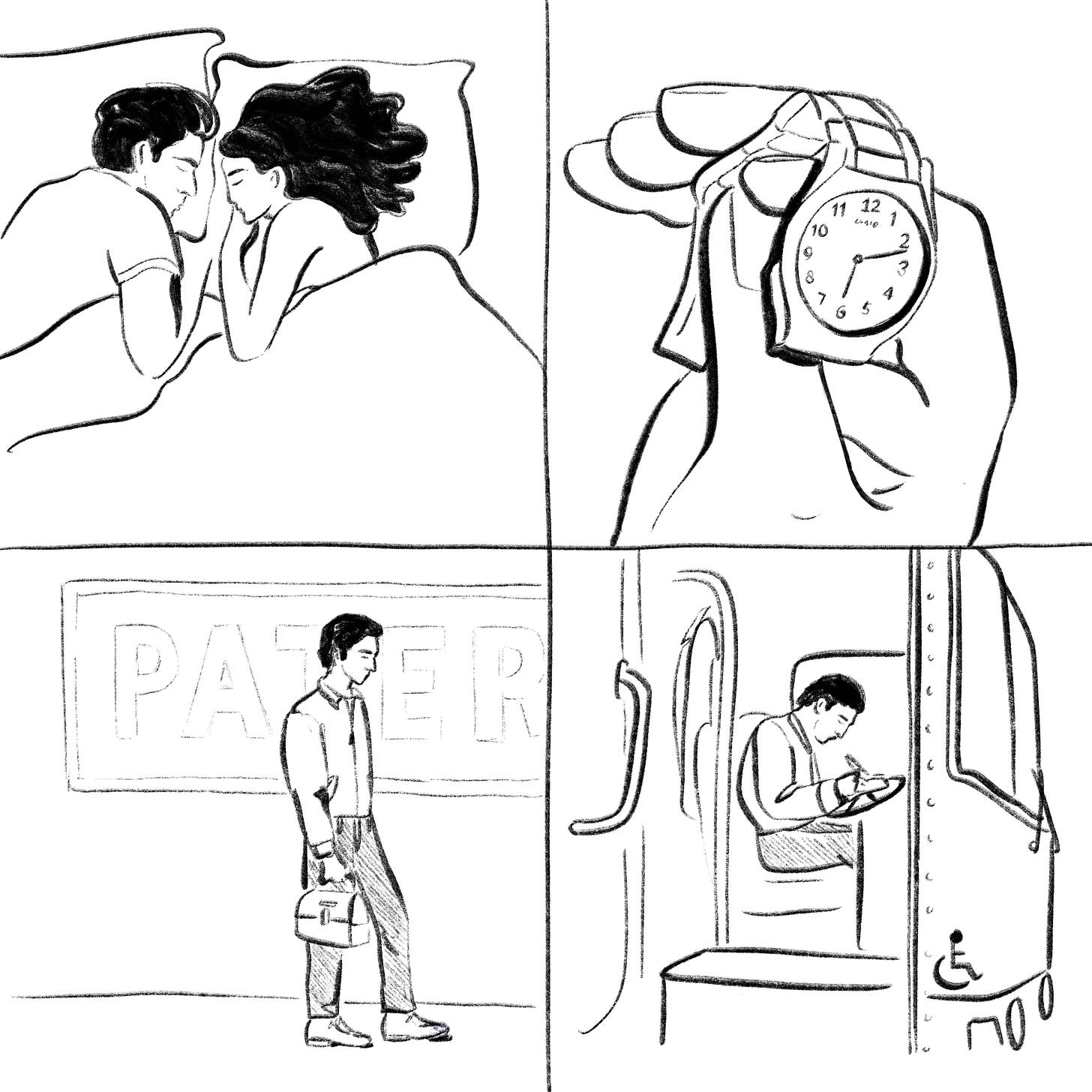

In both films, special attention is given to lunch breaks, an opportunity for each protagonist to practice their respective art. For Paterson, this consists of visiting the a bench by a waterfall, eating, and working on a poem in his leatherbound journal. He brings his meal in a rather adorable vintage Stanley lunch pale - a relic that represents his character as a whole. While the viewer is treated to a number of these poems throughout the film, Paterson is writing them almost entirely for himself. On occasion, he shares them with his partner who implores him to share them, ‘They should belong to the world, you know?’

Paterson’s lunch ritual

It is clear though, that Paterson does not want this. The artistic process is one that he engages in only for his love of it. Yes, it is incredibly routine. He writes his poems in the same place at the same time, every single day. But each time, he is conscious and present in doing so. He dedicates time to engaging with the world around him. An observational, slow, process that we watch happen, literally one word at a time as Paterson thinks aloud the words he pens (in voiceover). This is when a routine transforms into a ritual.

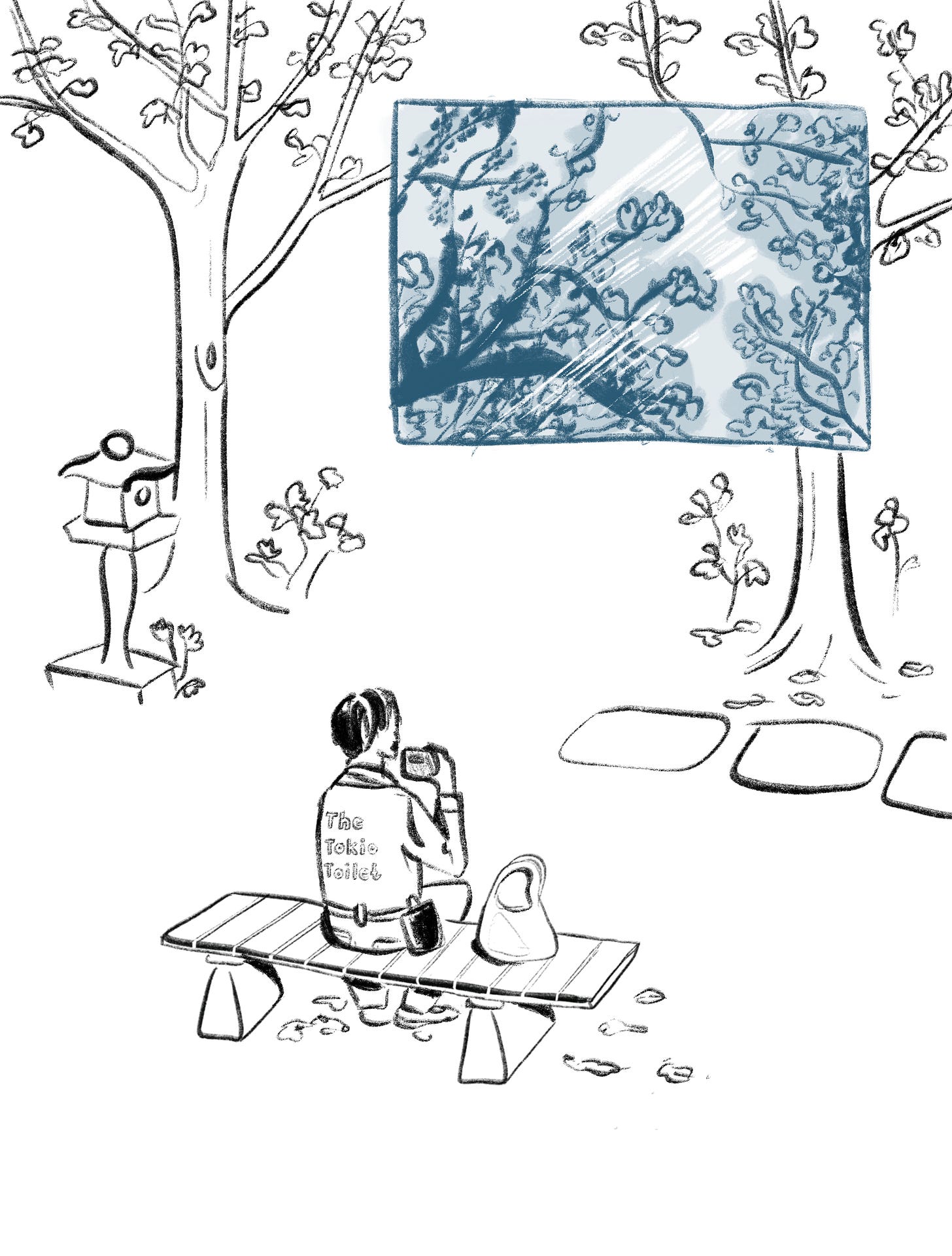

Hirayama also takes his lunch in the same spot every day: a little park with a smattering of trees amongst which he sits quietly. His artful practice is photography. Each day, the same subject: light pouring through the leaves and branches of the treetops. Later, we see him place the developed photos in meticulously organized boxes, with dates going back year after year. The photos, like the poems, are shown to no one. It’s documentation for himself alone. While Paterson’s poems cover a variety of subjects, Hirayama is uniquely focused, a routine in the extreme. They too, though, are a way in which he observes and engages with the world around him. An acute appreciation for the unnoticed and mundane. An attempt to capture something ephemeral - on no two days is the light exactly the same.

Hirayama’s lunch ritual

It’s unlikely that Michelle or I will be able to shed our smartphones or ever embody the energy of either of these two characters. We’re likely too distracted and too impatient. We can, however, look for ways in which we can appreciate and honor our routines, creating rituals out of obligations. We can work to create moments without distraction.

My morning commute consists largely of the rather miserable Paris metro, an odorous and droning 40 minutes that is unavoidable. However, the metro also provides a unique space with limited distractions. If I keep my phone locked up in my bag, I get to spend most mornings reading a book, an activity I often lack patience for in the evenings after a long day’s work. Now, I find that I miss my reading time when I don’t go to the office.

I love both of these films and they’re a great pairing. I wonder what you make of the differences between the poet creating and the cleaner capturing. I loved the concept of “komorebi” so much I had one of my Japanese students design a little sign with leaf shadows and the word in Japanese. Also, the bus driver having a romantic partner while the cleaner by chance given the opportunity to make a difference in his niece’s life, but otherwise being alone - how might that resonate? What would you pair with another favorite film of the last 5 years, Drive My Car?